When studying jazz guitar, you quickly learn that analyzing chord progressions and transposing chords are two essential skills you need to have down. But, while you know that analyzing and transposing is important, you might not know the quickest and easiest way to accomplish these goals. This is where Roman numerals come into play.

Roman numerals are used in music to analyze diatonic and non-diatonic chords as well as make transposing any chord or progression much easier on the guitar.

In this lesson, you learn what Roman numerals are, how they’re used in jazz analysis, and how to transpose chords with these numbers.

What You Will Learn in This Lesson

C Major Diatonic Chords With Roman Numerals

To begin your study of Roman numerals and their use in analysis and transposition, we will look at diatonic chords with Roman numerals.

Here are the notes in the key of C major, written on a single string, with the number of each note below the staff.

Arabic numbers are used to identify single-notes in jazz, like scale and arpeggio notes, while Roman numerals identify chords and progression.

This makes it easier to understand a written analysis of any line or progression, as you won’t be confused if you see 1 vs. I in an analysis.

Now you add chords on top of each of those C major scale notes to form the chords in the key of C major.

Here are those chords with the Roman numerals written underneath each chord to see how they line up in the key.

Notice that the Roman numerals are the same as the Arabic numbers, 1 is I, 2 is ii, etc., as each scale note gets a chord in the key.

Once you know the notes in a key, and their related chords, you can use that to analyze chord progressions.

Here’s an example of a common jazz chord progression with Roman numerals below each chord, from the key of C major.

Minor chords are written in lowercase roman numerals, while major and dominant chords are written in uppercase roman numerals.

A Minor Diatonic Chords With Roman Numerals

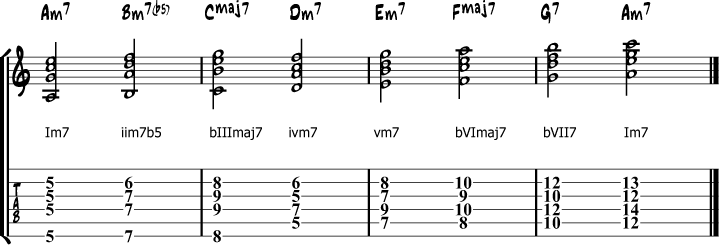

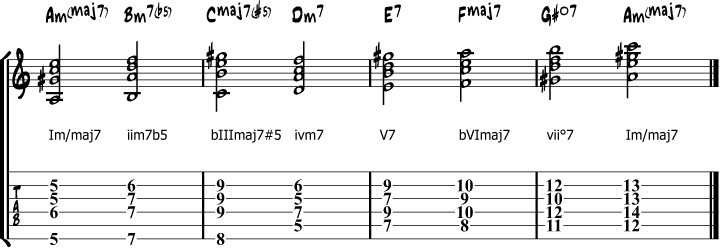

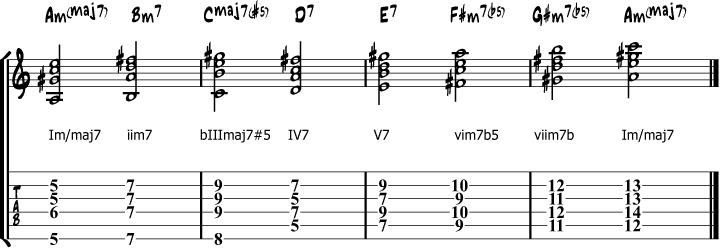

Here are the diatonic chords of the A natural minor scale (aka A Aeolian mode), with their Roman numbers:

In jazz (and music in general), we like a dominant chord on the V.

This is where the A harmonic minor scale comes in. Because the 7th note is a G#, the chord on V becomes E7 instead of Em7:

To complete, here are the chords of the A melodic minor scale:

Now that you know how to use Roman numerals to identify chords in a key, open your Real Book and analyze diatonic chords in any song you flip to.

If you can’t identify a chord in the key, then leave it for now until you study non-diatonic chords in the next section.

Secondary Dominant Chords

As well as seeing diatonic chords when using Roman numerals for analysis, you’ll also see non-diatonic chords.

In this lesson, we’ll look at two types of non-diatonic chords and how to analyze them with Roman numerals. These aren’t the only non-diatonic chords you’ll see when analyzing tunes, but they’re the most popular, so are essential to know.

The first non-diatonic chord is called a secondary dominant chord.

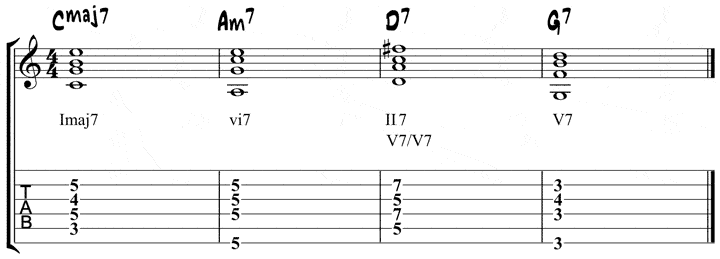

A secondary dominant chord is a V7 chord that isn’t the V7 of the key you’re in. Secondary dominant chords are written as V7/V7 or V7/iim7.

Examples of secondary dominants are V7 of V7, V7 of iim7, V7 of vim7, etc.

Or, you can use a shortcut such as II7 for V7/V7 or VI7 for V7/iim7, as both are commonly used in modern analysis.

I prefer to keep things close to the key, so I prefer II7 and VI7 for example, but try both and see which makes the most sense to you.

Here’s an example of a VI7 chord in the key of C major:

And here’s an example of a II7 chord in the key of C major:

Now that you know what secondary dominant chords are, grab a Real Book and identify secondary dominant chords in full tunes.

Secondary ii V Chords

As well as seeing secondary dominant chords, you also see secondary ii V chords in jazz progressions and tunes.

Secondary ii Vs function the same as secondary dominant chords, except you use a ii V leading to a diatonic chord rather than just a V7.

Here’s an example of a secondary ii V that leads to the iim7 in the key of C major, meaning Em7b5-A7b13 leading to Dm7.

Notice that the song doesn’t modulate to D minor, the secondary ii V is used to highlight the Dm7 chord, but not change to the full key of D minor.

Here’s another common example of a secondary ii V that Charlie Parker used a lot in his tunes.

In this example, the secondary ii V is used to highlight the vim7 chord (Am7), as well as acting as a transition bar between Imaj7 and vim7.

Now that you know what secondary ii V chords are, grab a fake book and identify secondary ii V chords in full tunes.

Take the A Train Analysis

Now that you know what Roman numerals are, and their common usage in jazz, you can look at them over an entire tune.

Here’s the chord progression to Take the A Train with Roman numerals below each chord in the tune.

Notice that I used the II7 rather than V7/V7 in bars 3 and 4 of the A section (D7).

You can use either analysis, but I prefer to relate Roman numerals to the key if possible to make it easier to transpose later on if needed.

Check out these changes, it’s a very diatonic progression with the exception of the D7 (V7/V7 (II7)) and the Gm7-C7 (iim7/IV and V7/IV).

Summertime Analysis

You can also use Roman numerals in minor keys, such as when analyzing and learning a song like Summertime, which is in D minor.

When using Roman numerals in minor keys all the same rules apply that you learned in major keys, with one exception.

Normally minor chords are written with a lowercase Roman numeral (iim7 for example), but in minor keys, the tonic chord uses a capital letter (Im7).

This is to signify that the tonic chord is special, it’s the resolution chord of the key, and therefore we use a capital letter to reflect that.

Here’s the Roman numeral analysis of Summertime.

Notice that there are three main chords in the song, Im7 (Dm7), ivm7 (Gm7), and Fmaj7 (bIIImaj7).

The rest of the chords are just ii-Vs that lead to those chords, so one diatonic ii V and two secondary ii V chords.

Transposing With Roman Numerals

Besides using Roman numerals to analyze and understand chord progressions, you also use them to make transposing easier on and off the guitar.

Here’s the chord progression for the first A section of Take the A Train, in the original key with Roman numerals underneath.

Now, to transpose this progression to another key, we’ll use F major as an example, you just need to know the Roman numerals and notes in the new key.

The notes in the key of F are F G A Bb C D E F, so all you do is move the Roman numerals from C to F and you have the same progression in a new key.

Here are the chords in F. Notice that the Roman numerals remain the same, but you’ve changed the chord symbols to be in the new key of F.

After you look at this example, see if you can write out the chords to the first A section of Take the A Train in other keys using the same approach.

Transposing chords on guitar is an essential skill to have, and Roman numerals make this skill easier to learn and quicker to apply in your playing.

In Secondary Dominant Chords, your second example was a II7 in C major, which you wrote as D7, which is correct. But below D7 you wrote IIm7, which is incorrect and just a typo, right?

Hi Scott, you’re right, thanks for letting me know. I fixed the typo…

I am from Germany where we do not use lower case Roman Numerals. I believe the USA is the only country using them in music theory. Think about it. When you write iimi7 you are basically saying: this is a minor chord ii=minor, and by the way, IT IS A MINOR CHORD mi=minor. Berklee College of Music has implemented a system called Roman Numeral Chord Symbols that is based entirely on Upper Case RNs, for example IImi7 instead of iimi7. In classical music, ii7 means play a minor chord based on the second scale degree of the key.

Your chord symbols are mixing (confusing) the classical and Berklee system. Although I have seen it many times, it is logistically wrong. It is not your fault. i have seen this in many popular music theory books in the US. Just a thought!

Examples of secondary dominants are V7 of V7, V7 of iim7, V7 of vim7, etc.

Or, you can use a shortcut such as II7 for V7/V7 or VI7 for V7/iim7, as both are commonly used in modern analysis

I’m confused here where does II7 comes from for a V7/V7, all ii’s minor, right?

Great lesson – good explanations.

Check: Cdim7 = root C and then 3 minor thirds stacked on top of each other –> c – es – ges – beses

Request: Would be nice if these lessons could be downloaded as pfd files – a lot easier than copying – cutting – pasting

Thanks for this article – I learnt a few things that I hadn’t been aware of before. Some follow-up questions:

1) Do you actually need to qualify diatonic major chords? That is, do you really need to specify chord type as being maj7, m7, m7b5 etc. as this is already implied by the Roman numeral (assuming the chord to be a seventh). I note that in your two examples of the C major scale harmonised in sevenths near the top of the article, the first uses unqualified Roman numerals.

2) Although you don’t explicitly state it, it seems that Roman numerals *always* relate back to the corresponding major scale degrees, even when using a minor scale. So for instance, the third chord in a minor sequence will always be a biii (bIII?) rather than a iii chord. Is that right?

3) How do you handle modulation in a general, non-key specific way?

4) How do you deal with inversions and slash chords?

Thanks.

1) Yes you do, because you can have secondary dominant chords and other items in major keys, like VI7, or II7.

2) They relate back to the tonic key, check out Summertime, Im7 is the tonic in minor.

3) You just state the new key above the first chord in that key then write the roman numerals in that key. If the song modulates to F major, just write “key of F” over the first chord then analyze in F from there.

4) We don’t normally write inversions unless they are slash chords, then you can just put Imaj7/3 if you want, but I find that confusing. I just put Imaj7 and people can see the / in the actual chord symbol.

Nice explanations. As far as transposing on guitar is concerned, I find it’s easier, once a song is known in one key, to simply move everything up or down, cutting out the middle part – working out what the new chords will be in the new key. I.e., pretend that the 3rd fret is now the 5th, etc. Capital on root in a minor key is a new one, but makes sense. What happened to II7(b5) in A Train? Charles – in minor key, the relative major chord will be ‘III’ not ‘bIII’.

Please sir, I don’t understand licks and staff. Can you be of aid to me?

It works for standards and some modern tunes, but not all. Not sure what you mean by not correct, Gm7 is the ivm7 and Em7b5 is th iim7b5.

Sorry, I see what you mean, and I take back the “correction”!

The example does show that the notation obscures—more than it illuminates—the basic relation between a minor key and its relative major. (“bIII” looks complicated; but these bars are a simple modulation, aren’t they?).

What *is* a tonic, after all?

It’s interesting to notice what a notation system makes more clear and what it makes less clear. The examples show that jazz occupies a lot of strange territory among different theoretical systems. Though “Fee Fi Fo Fum” and “House of Jade” are hard to put into this system, “Giant Steps” is easy. That’s a neat historical tipping point!

Several Roman numerals are wrong in “Summertime.” For example, not ii but iv.

This all assumes tonal harmony. Is this notation useful (or possible) with a tune like “Fee Fi Fo Fum”?

You missed the “/bIII” there. So, he’s not saying that Gm7 is the ii chord in Dm; he’s saying that Gm7 is the ii chord in F, which is the bIII of D minor.

You see secondary dominants done this way all the time, such as V/ii (“five of two”), V/V (“five of five”), etc. This is just an extension of that concept. So instead of just V/V (“five of five”), for example, it’s a ii/V – V/V (“two of five, five of five”). In other words, it would be a ii-V progression in the key of the five chord.

In this instance, it’s a ii-V progression in the key of the bIII chord.

Very cool lesson! This is something you don’t see covered much. Nice explanations/descriptions. Thanks for posting it!

Cool lesson really but there is still something unclear for me. What could I play when I have a secondary dominant.It is clear for me that I will be right if I play the two chords but is this the only way to do?

You can add them before any chord when comping or soloing, but until you get to the intermediate or advanced level of playing, it’s more to know how to recognize them when you see them in a song so you know what that chord is and how to deal with it.